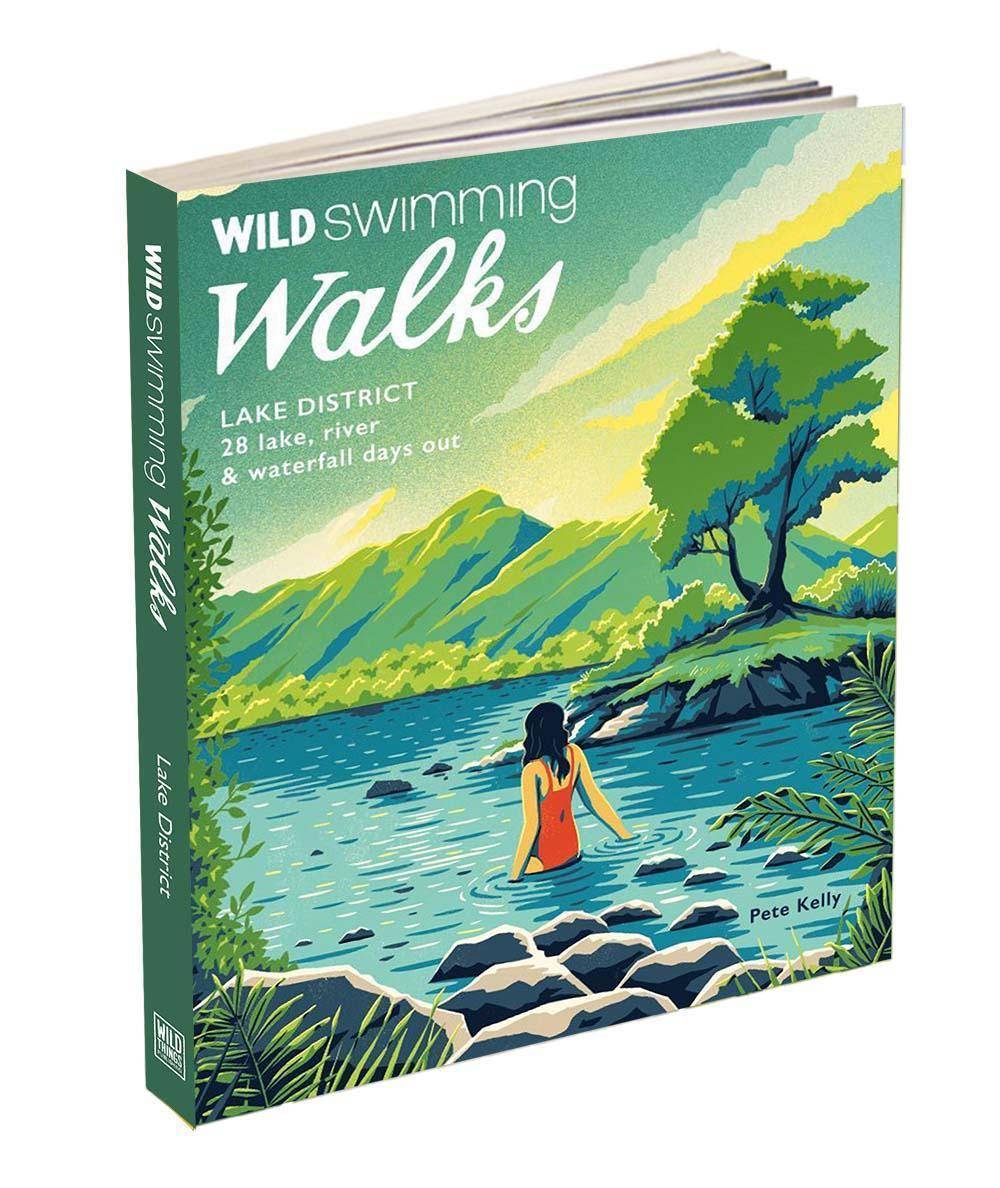

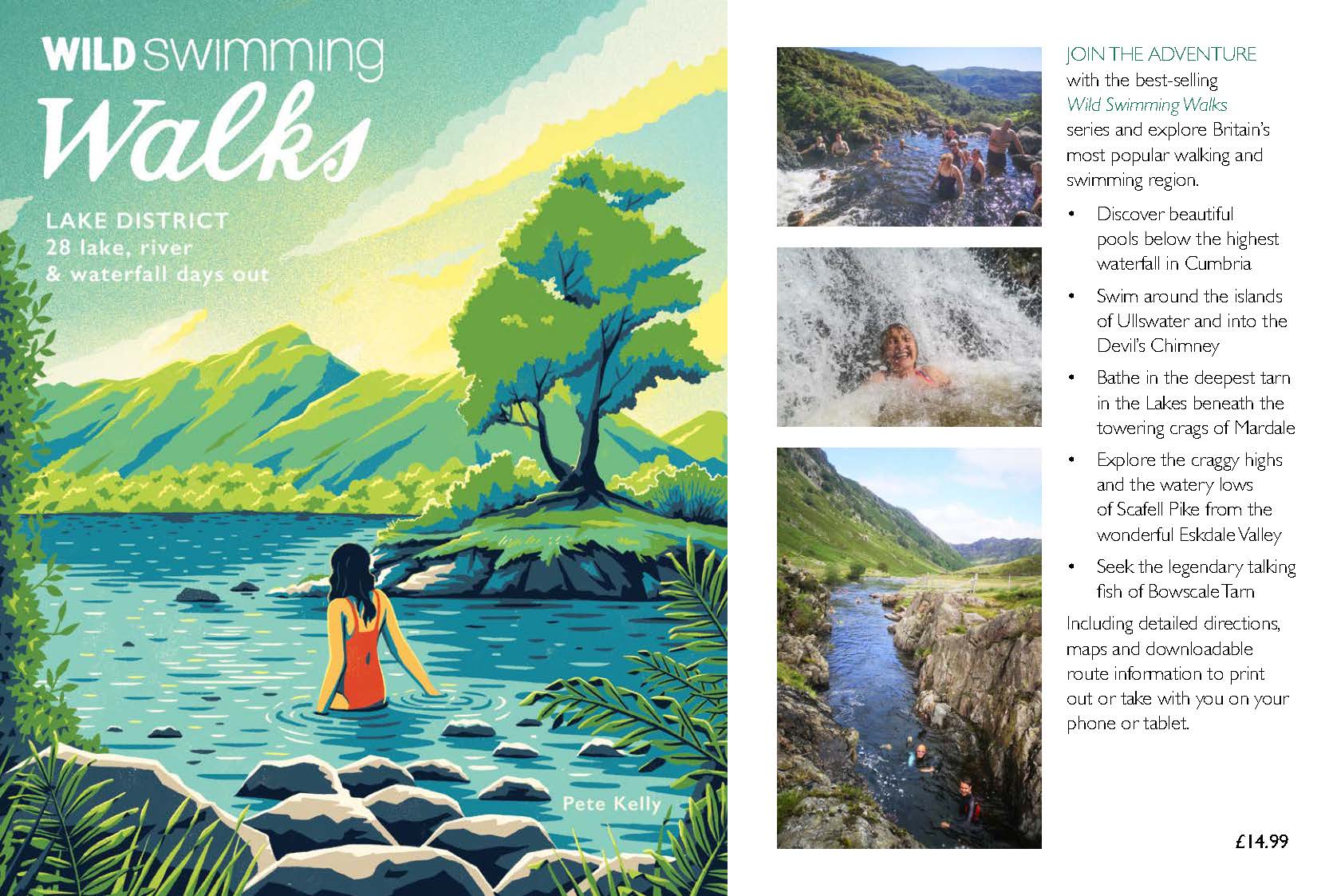

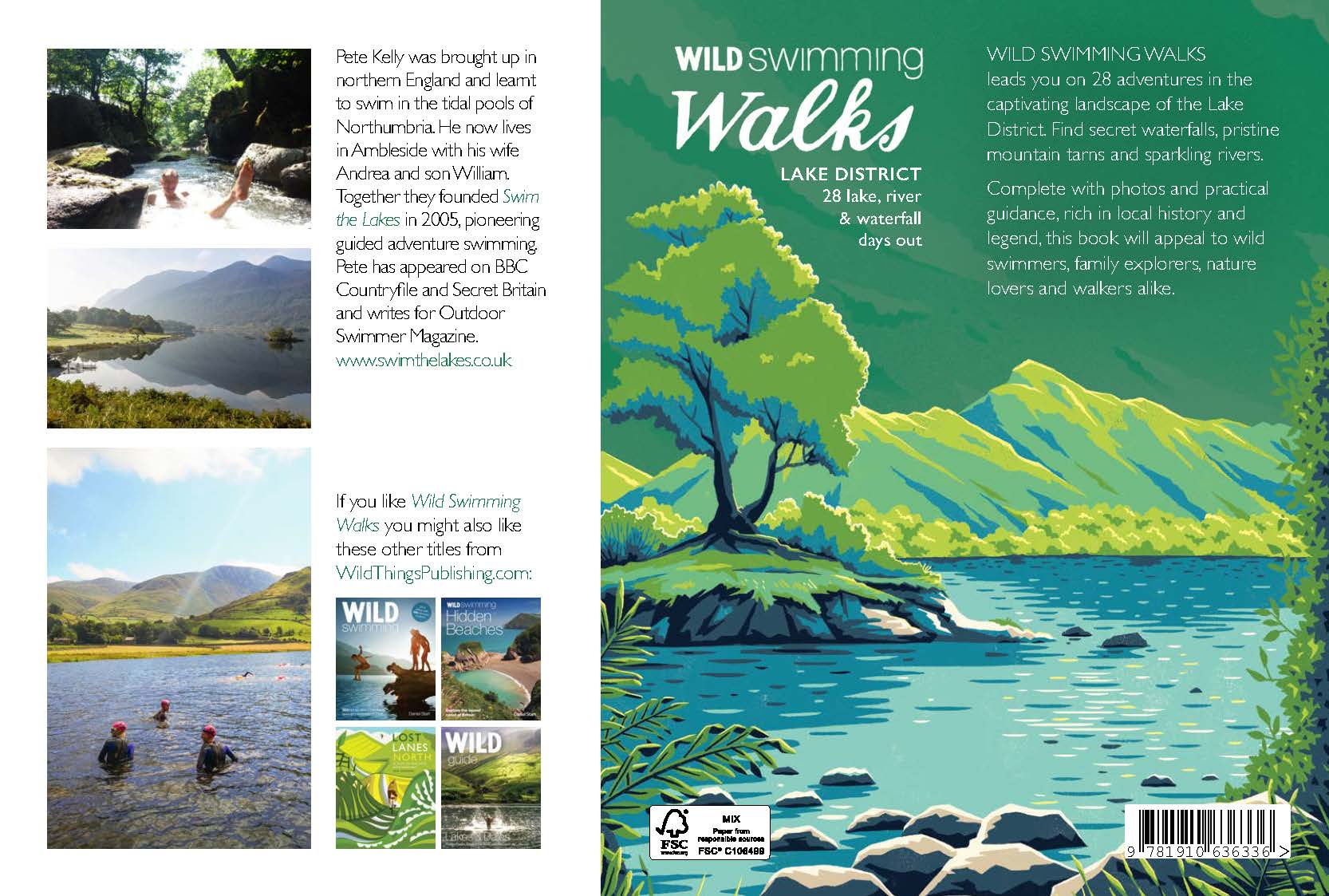

Wild Swimming Walks leads you on 28 adventures in the captivating landscape of the Lake District. Find secret waterfalls, pristine mountain tarns and sparkling rivers.

Complete with photos and practical guidance, rich in local history and legend, this book will appeal to wild swimmers, family explorers, nature lovers and walkers alike.

* Discover beautiful pools below the highest waterfall in Cumbria

* Swim around the islands of Ullswater and into the Devil’s Chimney

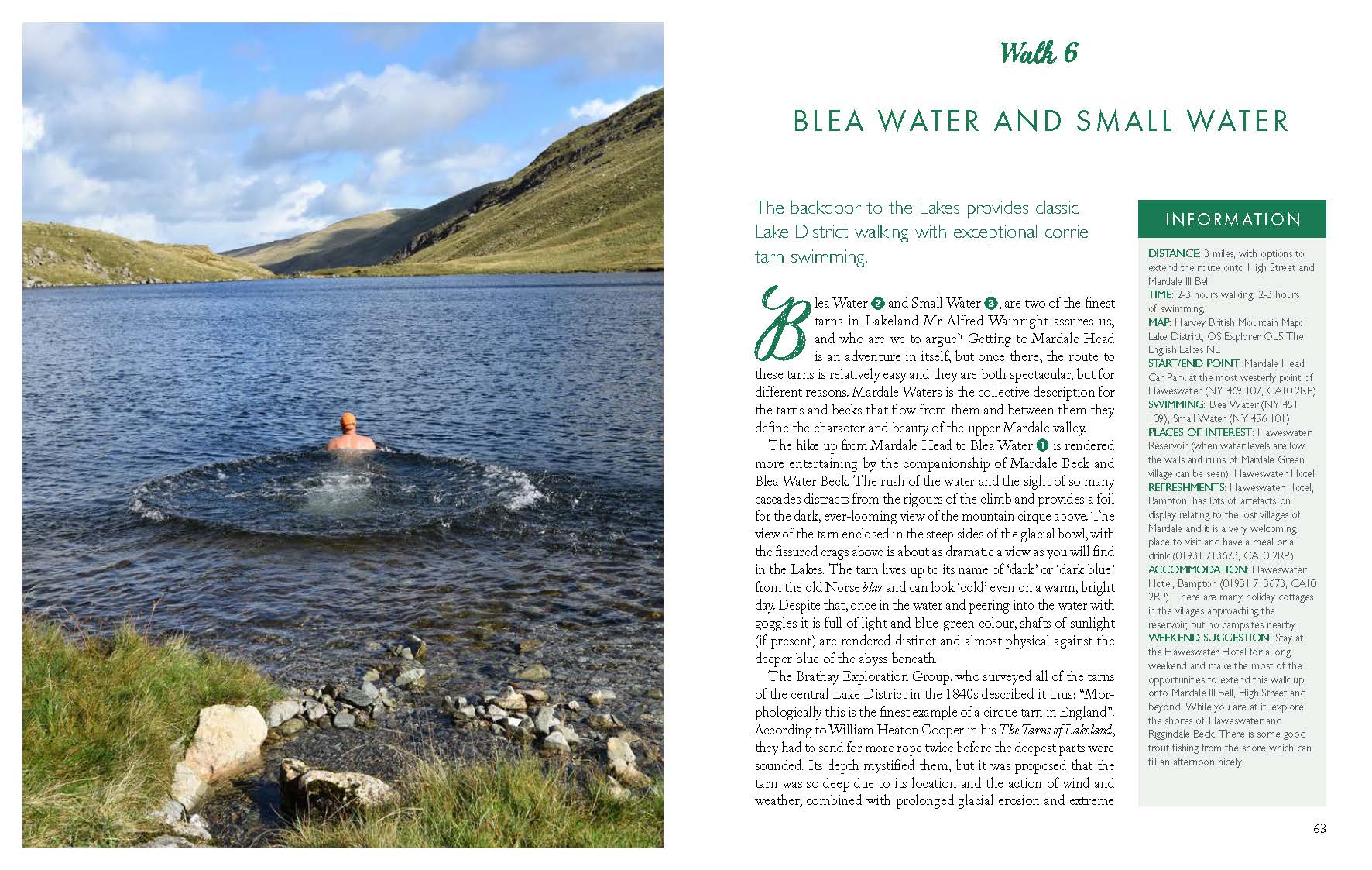

* Bathe in the deepest tarn in the Lakes beneath the towering crags of Mardale

* Explore the craggy highs and the watery lows of Scafell Pike from the wonderful Eskdale Valley

* Seek the legendary talking fish of Bowscale Tarn

Including detailed directions, maps and downloadable route information to print out or take with you on your phone or tablet.

Pete Kelly was brought up in northern England and learnt to swim in the tidal pools of Northumbria. He now lives in Ambleside with his wife Andrea and son William. Together they founded Swim the Lakes in 2005, pioneering guided adventure swimming. Pete has appeared on BBC Countryfile and Secret Britain and writes for Outdoor Swimmer Magazine.

www.swimthelakes.co.uk

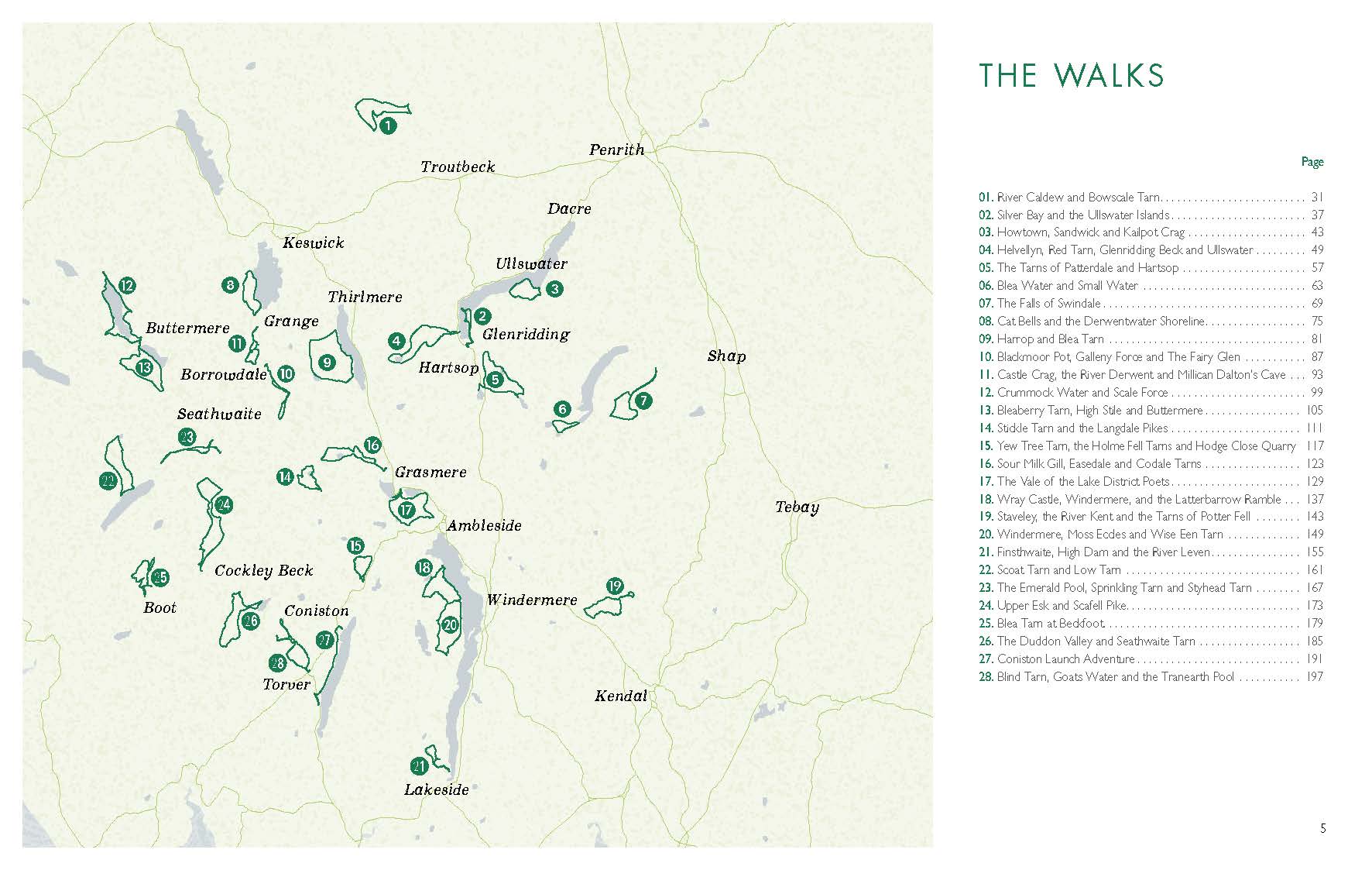

Table of Contents

Routes included:

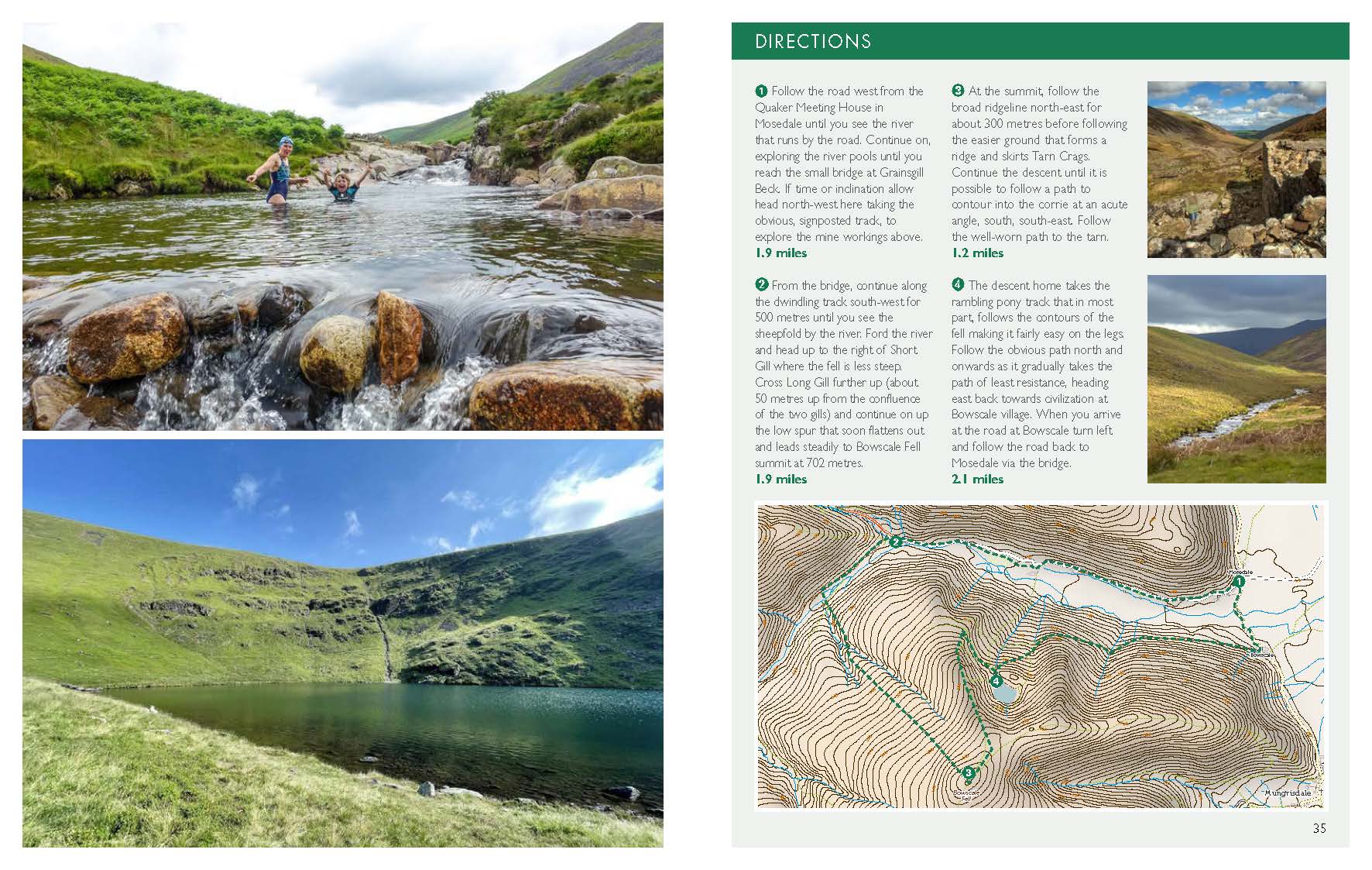

River Caldew and Bowscale Tarn

Silver Bay and the Ullswater Islands

Howtown, Sandwick and Kailpot Crag

Helvellyn, Red Tarn, Glenridding Beck and Ullswater

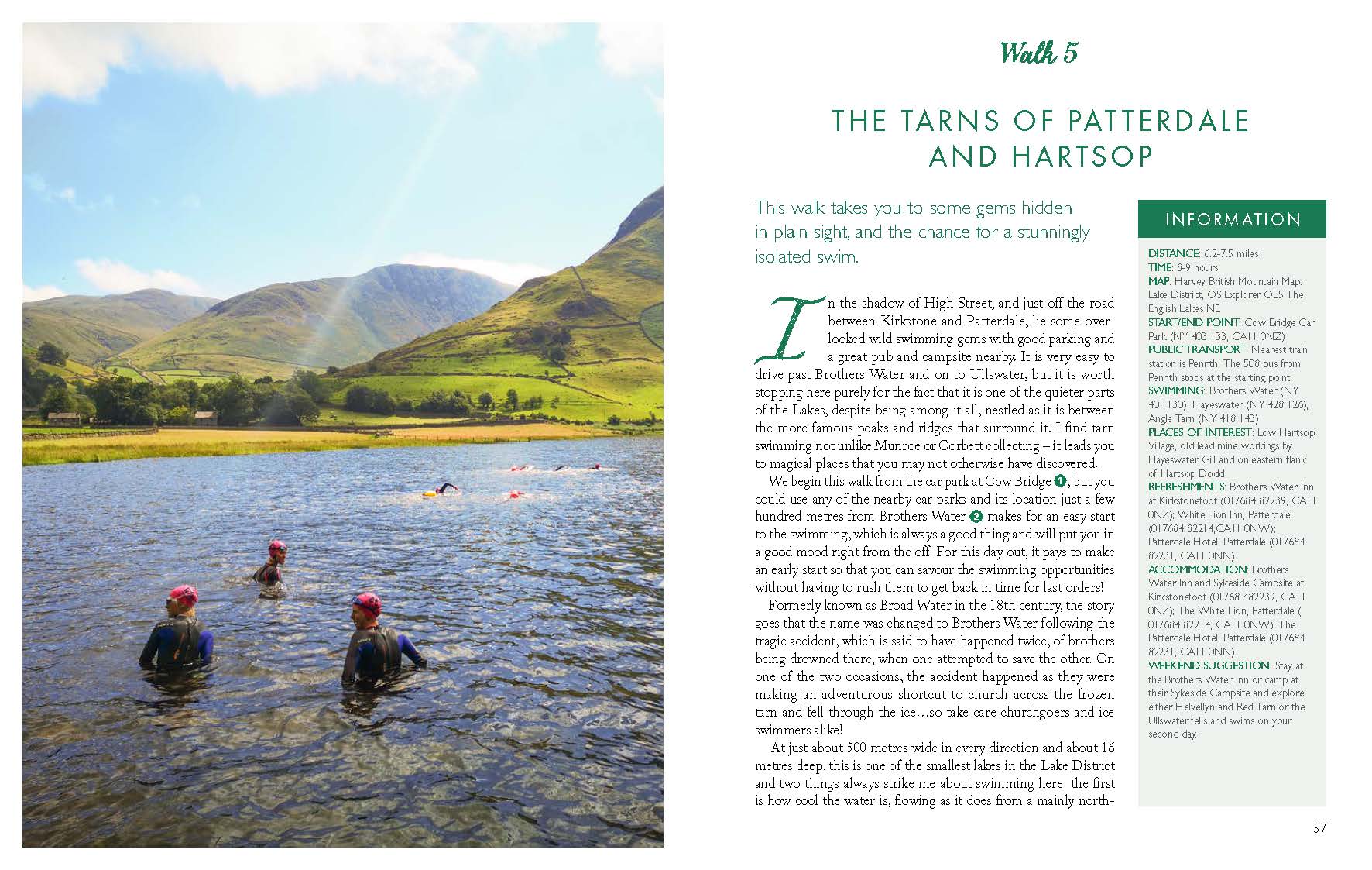

The Tarns of Patterdale and Hartsop

Blea Water and Small Water

The Falls of Swindale

Cat Bells and the Derwentwater Shoreline

Harrop and Blea Tarn

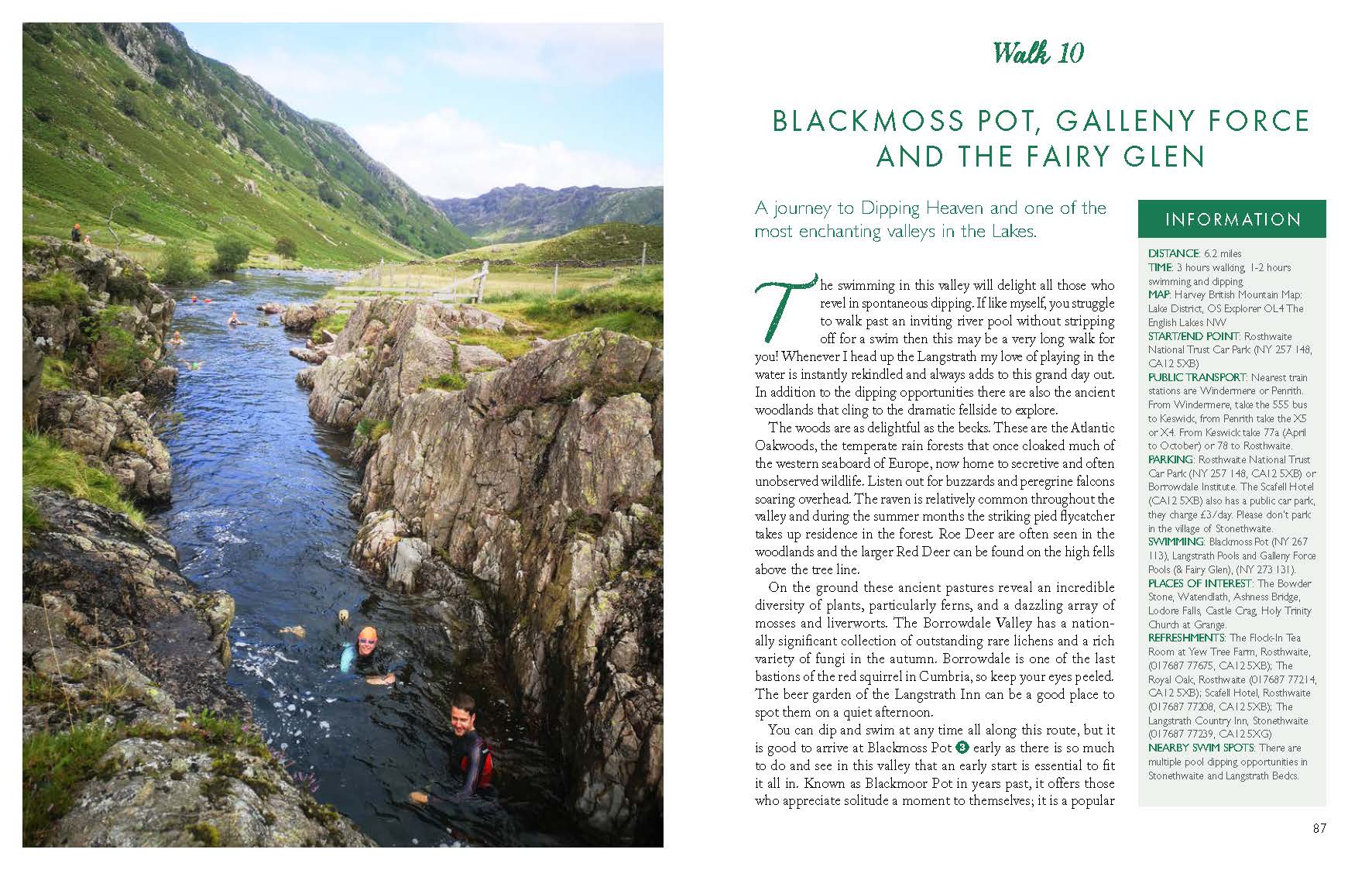

Blackmoor Pot, Galleny Force and The Fairy Glen

Castle Crag, the River Derwent and Millican Dalton’s Cave

Crummock Water and Scale Force

Bleaberry Tarn, High Stile and Buttermere

Stickle Tarn and the Langdale Pikes

Yew Tree Tarn, the Holme Fell Tarns and Hodge Close Quarry

Sour Milk Gill, Easedale and Codale Tarns

The Vale of the Lake District Poets

Wray Castle, Windermere, and the Latterbarrow Ramble

Staveley, the River Kent and the Tarns of Potter Fell

Windermere, Moss Eccles and Wise Een Tarn

Finsthwaite, High Dam and the River Leven

Scoat Tarn and Low Tarn

The Emerald Pool, Sprinkling Tarn and Styhead Tarn

Upper Esk and Scafell Pike

Blea Tarn at Beckfoot

The Duddon Valley and Seathwaite Tarn

Coniston Launch Adventure

Blind Tarn, Goats Water and the Tranearth Pool

Introduction

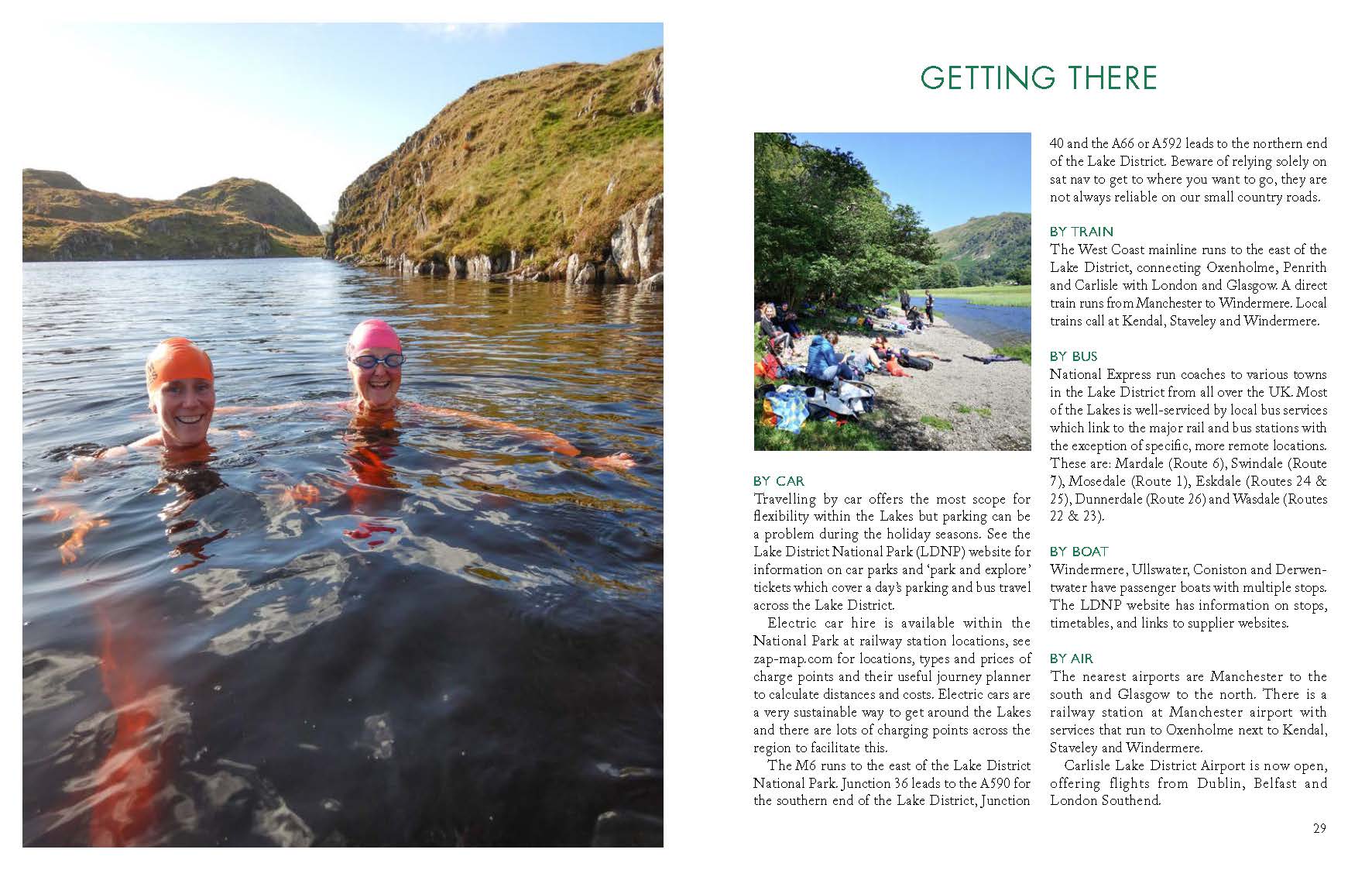

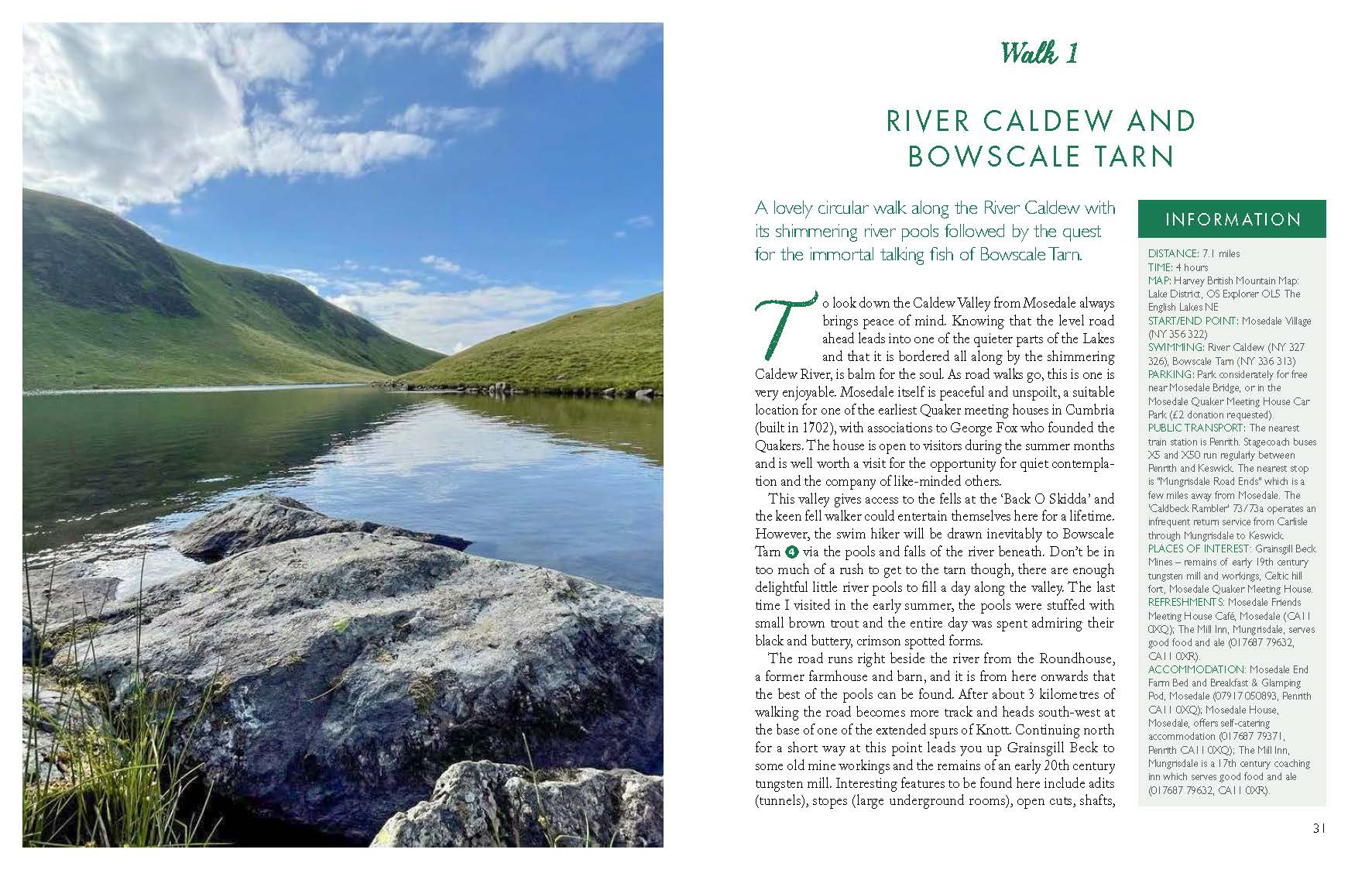

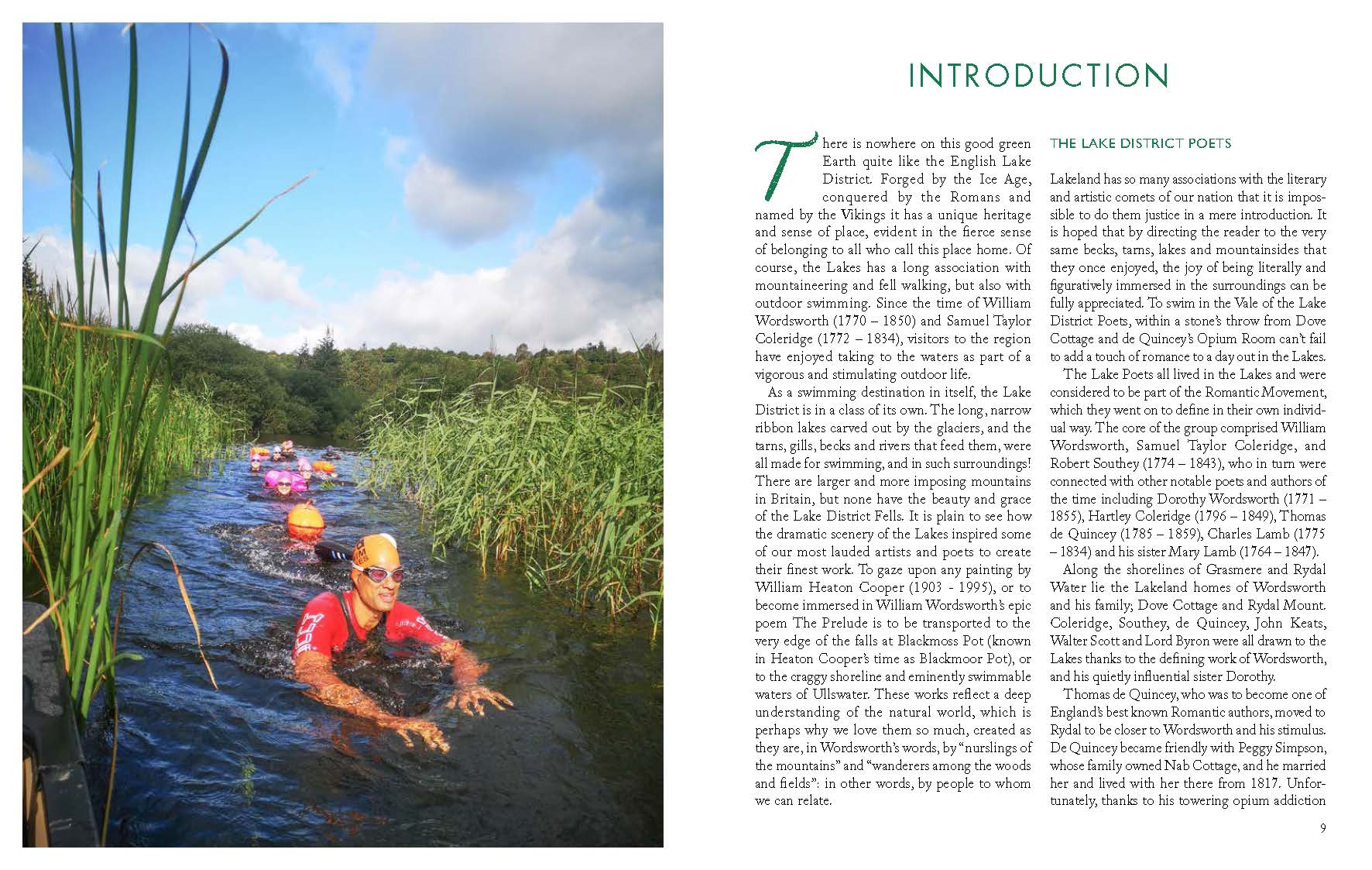

There is nowhere on this good green Earth quite like the English Lake District. Forged by the Ice Age, conquered by the Romans and named by the Vikings it has a unique heritage and sense of place, evident in the fierce sense of belonging to all who call this place home. Of course, the Lakes has a long association with mountaineering and fell walking, but also with outdoor swimming. Since the time of William Wordsworth (1770 – 1850) and Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772 – 1834), visitors to the region have enjoyed taking to the waters as part of a vigorous and stimulating outdoor life.

As a swimming destination in itself, the Lake District is in a class of its own. The long, narrow ribbon lakes carved out by the glaciers, and the tarns, gills, becks and rivers that feed them, were all made for swimming, and in such surroundings! There are larger and more imposing mountains in Britain, but none have the beauty and grace of the Lake District Fells. It is plain to see how the dramatic scenery of the Lakes inspired some of our most lauded artists and poets to create their finest work. To gaze upon any painting by William Heaton Cooper (1903 – 1995), or to become immersed in William Wordsworth’s epic poem The Prelude is to be transported to the very edge of the falls at Blackmoss Pot (known in Heaton Cooper’s time as Blackmoor Pot), or to the craggy shoreline and eminently swimmable waters of Ullswater. These works reflect a deep understanding of the natural world, which is perhaps why we love them so much, created as they are, in Wordsworth’s words, by “nurslings of the mountains” and “wanderers among the woods and fields”: in other words, by people to whom we can relate.

The Lake District Poets

Lakeland has so many associations with the literary and artistic comets of our nation that it is impossible to do them justice in a mere introduction. It is hoped that by directing the reader to the very same becks, tarns, lakes and mountainsides that they once enjoyed, the joy of being literally and figuratively immersed in the surroundings can be fully appreciated. To swim in the Vale of the Lake District Poets, within a stone’s throw from Dove Cottage and de Quincey’s Opium Room can’t fail to add a touch of romance to a day out in the Lakes.

The Lake Poets all lived in the Lakes and were considered to be part of the Romantic Movement, which they went on to define in their own individual way. The core of the group comprised William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Robert Southey (1774 – 1843), who in turn were connected with other notable poets and authors of the time including Dorothy Wordsworth (1771 – 1855), Hartley Coleridge (1796 – 1849), Thomas de Quincey (1785 – 1859), Charles Lamb (1775 – 1834) and his sister Mary Lamb (1764 – 1847).

Along the shorelines of Grasmere and Rydal Water lie the Lakeland homes of Wordsworth and his family; Dove Cottage and Rydal Mount. Coleridge, Southey, de Quincey, John Keats, Walter Scott and Lord Byron were all drawn to the Lakes thanks to the defining work of Wordsworth, and his quietly influential sister Dorothy.

Thomas de Quincey, who was to become one of England’s best known Romantic authors, moved to Rydal to be closer to Wordsworth and his stimulus. De Quincey became friendly with Peggy Simpson, whose family owned Nab Cottage, and he married her and lived with her there from 1817. Unfortunately, thanks to his towering opium addiction and his associated debts they were forced to move out in 1833. Hartley Coleridge, the son of Samuel Taylor Coleridge moved into the cottage and remained there until his death in 1849. Mercifully, Dove Cottage, Rydal Mount and Nab Cottage have retained their original character and are very much worth visiting if only for an excuse to be close to the two most perfectly formed swimming lakes in the region: Grasmere and Rydal Water. Taken as a whole, the charming lake-filled vale and the handsome old homes of our most beloved poets and their attendant ghosts, compliment any exploration, by land or by water.

Literary Connections to the Water

Adults of a certain age may have been reared on the wonderful tales of Beatrix Potter (1866 – 1943) and perhaps later on, those of Arthur Ransome (1884 – 1967) and his Swallows and Amazons adventures. Both authors display an understanding and appreciation of the wildlife and landscape of the Lake District as well as its potential for adventure. From a swimming perspective, both authors do us proud and express the inner child’s sense of wonder and exploration. Reliving childhood dreams must be considered one of the many pleasures of adulthood and to do it whilst swimming outdoors can’t be beaten.

From the stories in his books, Ransome gives us the Octopus Lagoon (Allan Tarn on the River Crake), Rio (Bowness-on-Windermere) and Wildcat Island (Peel Island on Coniston Water, see chapter 27), all wonderful places to swim in their own right, but all the more evocative if you were raised on the Swallows and Amazons stories. Beatrix Potter has given us so much more: she was a committed conservationist and was ahead of her time in recognising the problems of afforestation and the importance of biodiversity. She was the champion of our beloved Herdwick sheep and Belted Galloway cattle and invested much of her own money into land preservation and property restoration so that others could benefit from them (she left most of her land and property to the National Trust).

Potter was best known as a children’s author and as a brilliant artist and illustrator (her work has been curated to good effect at The Armitt Museum in Ambleside and is worth visiting). As swimmers we can thank her for the preservation of Moss Eccles Tarn (see chapter 20) and with the places associated with her books, in particular The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin. Squirrel Nutkin is based on the adventures of the impertinent squirrel, Nutkin, and his friends who sail over to Owl Island (St Herbert’s Island, Derwentwater; see chapter 8) on tiny rafts using their tails as sails. Nutkin incurs the wrath of Old Brown the owl and barely escapes minus his tail! There are few hazels on St Herberts Island these days, although I’ve heard an owl hunting there late at night, and the swim out to the island will forever be a favourite of mine.

Art and Water

As a young watercolour artist and mountaineer, I remember feeling incredibly self-conscious while attempting to capture the grandeur of Great Langdale with paint and brush, whilst perched on Raven Crag. Later on, I happened to be in Grasmere where I noticed for the first time the Heaton Cooper Gallery. Embarrassment never troubled me again and the works of William Heaton-Cooper (1903 – 1995) will remain an inspiration forever. The Heaton Cooper dynasty is as hefted to the Lakeland fells as the sheep that graze upon them. Alfred Heaton-Cooper (1863 – 1929), his son William, William’s wife, the sculptor Ophelia Gordon Bell (1915 – 1975) and their son Julian Cooper (born in 1947), have all portrayed the county in their own unique styles and their work can be appreciated at their Grasmere Studio (still run by the family, Julian Cooper and Becky Heaton Cooper, William’s daughter).

Although there have been many exceptional artists that have painted the Lakes, none capture the experience of being there in person and the sheer grandeur and scale of the fells, like William Heaton Cooper (except perhaps Turner). He is recognised as one of the most celebrated British landscape artists of the 20th century and was also a great writer. He produced the seminal tarn guide, The Tarns of Lakeland, which is illustrated with his wonderful watercolours and sketches; essential bedtime reading for any aspirant swim-hiker. It is apparent from his writing that the whole family were partial to a spot of mountain swimming, and he is clearly drawn to the water in all of its permutations. His depiction of water and its depth and clarity so typical of the Lake District is exceptional and as well as painting most of the tarns featured in this book, he painted all of the lakes in it too.

One cannot mention art in the Lake District and not include the talented John Ruskin (1819 – 1900). Ruskin was the leading English art critic of the Victorian era, as well as a gifted draughtsman and watercolourist. He looked to cause positive cultural and social change through his work and was considered to be an important example of a Victorian Sage (what we might now call an ‘influencer’). His detailed sketches and paintings can be seen at his former home of Brantwood on Coniston. Ruskin lived at Brantwood for the last 28 years of his life and died in the Lake District in 1900. Brantwood, as well as the Ruskin Museum in Coniston are well worth a visit not just to view his artistic work; they offer a glimpse of the Lake District as it once was and a hint at what it was to become.

History of the Land

Much of the character and appearance of the Lake District countryside is far from natural; man has made his mark here since the Stone Age. Since this time the rocks and minerals hidden within the mountains have been sought after and exploited, facilitated in time by the accessible ports of the west coast. There are in excess of 300 different minerals to be found in the Lake District and lead, copper, zinc, tungsten, graphite, slate and coal are among the many that have been mined and quarried. Much of the mineral exploitation continued up until the Industrial Revolution and beyond.

Mines and slate works litter the county. Some remain valued and productive, but time has reclaimed the defunct ones, healing the scars of the past. Moss and fern have softened the edges of the spoil heaps and water has filled the old quarries, creating some fascinating places to swim (see chapter 15, for Hodge Close Quarry). Many of the water supplies that served the industrial past of the Lakes remain and also provide us with some classic swimming venues like the tarns of Potter Fell (see chapter 19), and Seathwaite Tarn in the Duddon Valley (see chapter 26). Most of them are dammed tarns and some are still used as reservoirs to supply homes and businesses today (see chapter 14 for Stickle Tarn).

The traditional farming methods of Cumbria also continue to leave their mark on the land. Most of the meadows in mountainous valleys like the Duddon and Wasdale have been hard-won through the sweat and toil of generations of farmers. The vast stone mounds, or clearance cairns at Wasdale Head are testimony to their work. These mounds and much of the walling material has been hand-cleared from the ground over centuries. The grazing habits of everyone’s favourite sheep, the Herdwick, have a lot to do with how our fells appear to the eye. They crop the fellside grass so short it looks like newly mowed lawn in places, anything green and succulent doesn’t stand a chance of growing. Indeed, you’ll often see a lone sheep penned in local gardens to keep the lawn in order and to feed it with manure. The environment they create upon the fells is considered to be artificial by some and quintessentially Cumbrian by others – hopefully the planned rewilding of parts of the Lake District will leave room for our sheep and their bemused smiling faces, they are good company on a grim day on the fells in winter.

Early Explorers

Written guides to the Lake District fells are many and varied. The first, and one of the best, was Guide to the Lakes written by Wordsworth himself in 1810. The guide was initially published anonymously, was then updated and expanded over a number of editions until the sought after 1835 fifth edition was published. Guide to the Lakes is typical Wordsworth and, already recognised as a place of beauty, drew the great and the good to the Lakes in increasing numbers.

“The Guide is multi-faceted. It is a guide, but it is also a prose-poem about light, shapes and textures, about movement and stillness … What holds this diversity together is the voice of complete authority, compounded from experience, intense observation, thought and love.”

The distinguished guidebook writer Mountford John Byrde Baddeley (1843–1906) took up the baton in 1880 when he published his Thorough Guide to the English Lake District. This became a real favourite of visitors to the Lakes in the 19th and well into the 20th century and remained in print into its 26th edition. The advice given was very general and included details of low-level walks and accommodation and travel advice. There were many other guidebook writers of the age of course, all with their own particular character and many of the better guides focusing on the blossoming post-war rock climbing scene led by A. Harry Griffin (1911 – 2004) and his Coniston Tigers (see The Coniston Tigers: Seventy Years of Mountain Adventure by A. Harry Griffin for more). Griffin was at heart a climber but loved to ski and swim too, sometimes in the same outing! He is probably the first person to actively seek out the Lake District tarns, swim them all and document it in his many fascinating publications. But I digress… The guidebooks scene was in Baddeley’s hands for many years. Then along came A.W.

A misanthrope with a sense of humour Alfred Wainwright MBE (1907-1991) was infatuated with the Lake District and was a keen fellsman and a brilliant illustrator. From his humble, working-class background he became Britain’s leading authority on fell walking in the Lakes, albeit rather reluctantly. His seven-volume Pictorial Guide to the Lakeland Fells, consisted entirely of duplications of his original hand-written volumes and was published between 1955 and 1966. Even now, 67 years after his first publication, his revised and updated guides remain the standard reference work to the 214 fells of the Lake District documented in his books. It is fair to say that amongst fellow outdoors folk he is considered a National Treasure.

The 214 fells covered in A.W.’s Pictorial Guides are considered ‘Wainwrights’ in his honour. They are as sought after in England as Munros are in Scotland. It is certain that Wainwright did not intend to classify the Cumbrian fells in any way, he merely detailed his favourite routes to the top of his favourite fells. But he left a legacy that many ‘Wainwright Baggers’ are grateful for and poring over his exquisite guidebooks prior to any fell walking adventure is considered part of the journey to the summit. The Long Distance Walker’s Association (LDWA) holds a register of walkers who have successfully completed all of the Wainwrights.

There are also ‘Birketts’ and ‘Marilyns’ in the Lake District. Wainwright didn’t cover every peak in the Lake District. Birketts are based on the excellent guidebooks of local man Bill Birkett. There are 541 Birketts, many of which are also Wainwrights, they include all of the peaks within the boundary of the Lake District National Park that are over 1,000ft (305m).

A Marilyn is a peak with a prominence over 490ft (150m) regardless of their overall height. The list is very long at 2,011 and includes hills all over the British Isles. They were created by hillwalker and author Alan Dawson and listed in his 1992 book The Relative Hills of Britain. He named then after Marilyn Monroe. A tongue-in-cheek nod to the Munros of Scotland.

On the ninth of July 2017, the Lake District became a UNESCO World Heritage Site, joining some of the world’s most iconic locations, including Hadrian’s Wall and the Taj Mahal, recognising it as a world-class cultural landscape.

The sheer scale of opportunity to engage in classic English hillwalking is overwhelming in the Lake District. This book hopes to combine some of these classic walks with equally satisfying swims and where possible, to link them to the cultural and historical character of Cumbria. Thankfully, with so much water and heritage to play with this was not too difficult a task. Since childhood I have been lucky enough to walk, climb and swim in this, the most beautiful corner of our country and trust that by sharing some of its secrets the reader will benefit from what it can give.