Publishes 1st May 2026 – order now for shipping in late April

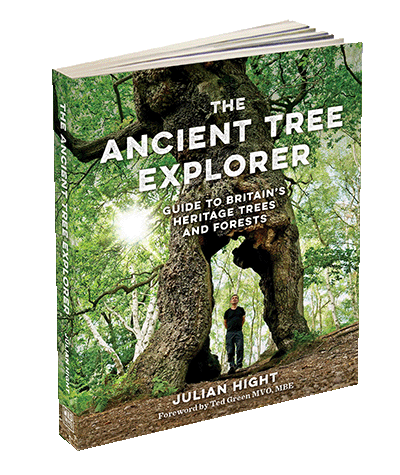

By Julian Hight, Foreword by Ted Green MVO, MBE

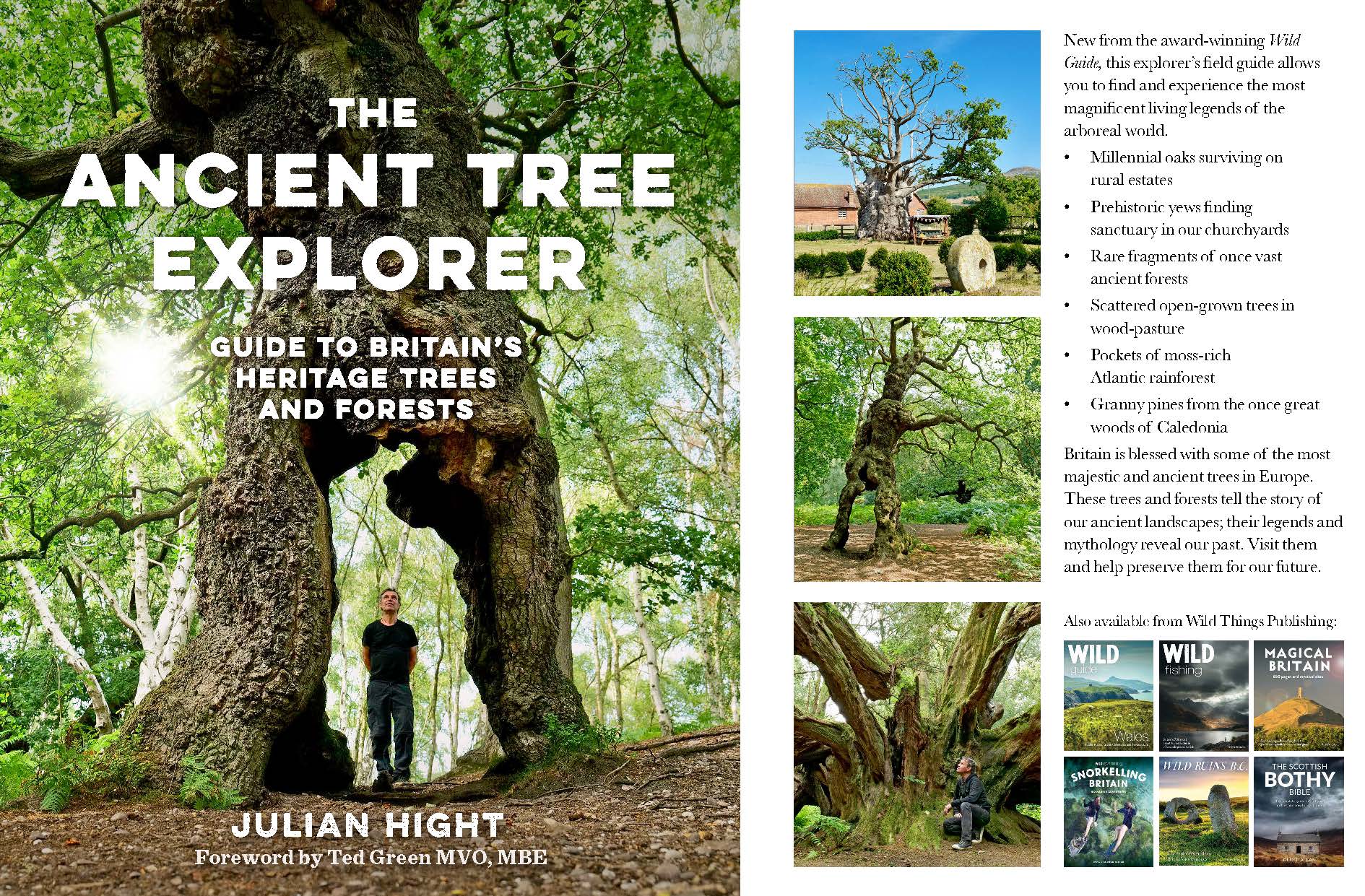

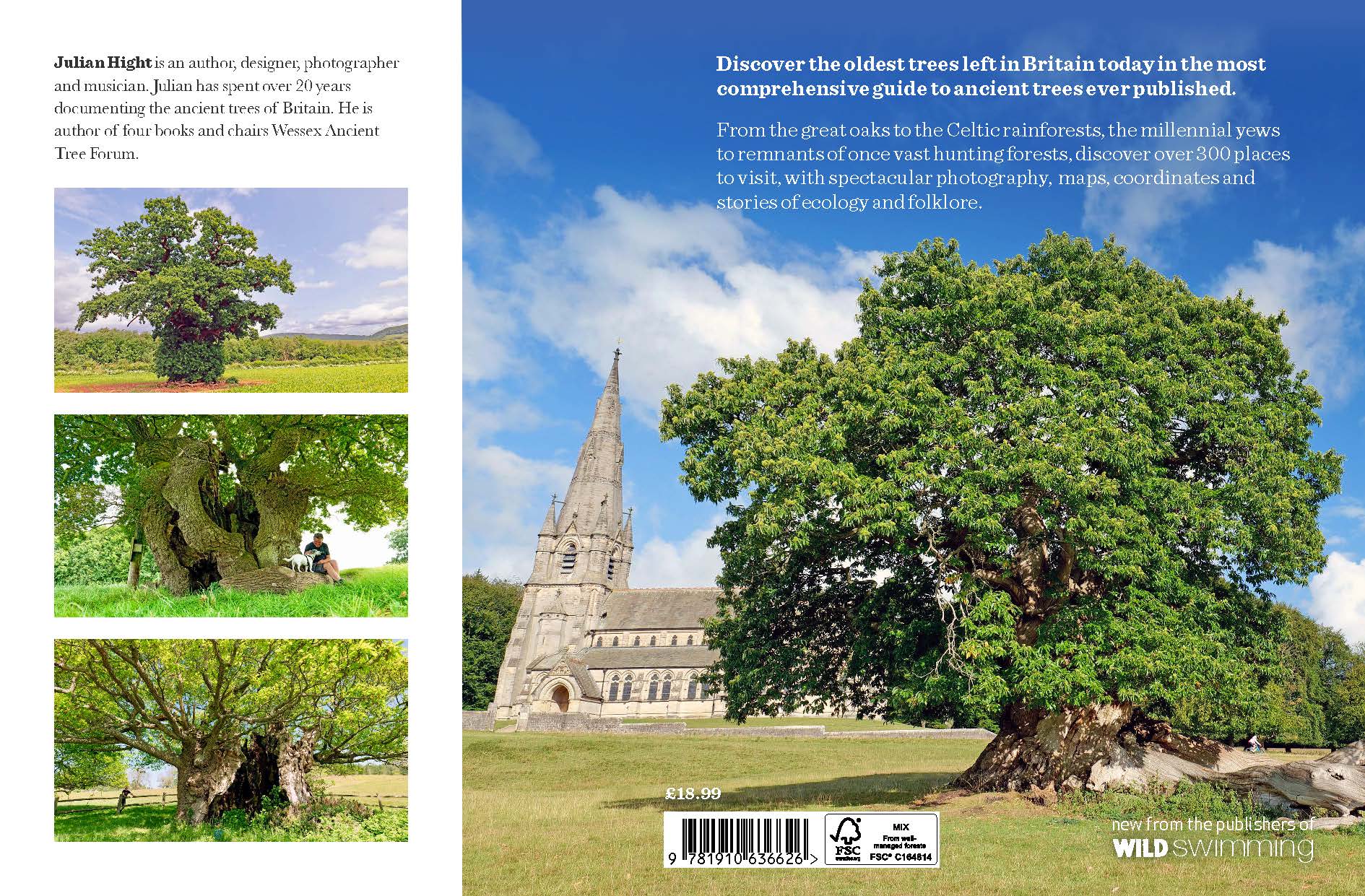

Discover the oldest trees left in Britain today in the most comprehensive guide to ancient trees ever published.

From the great oaks to the Celtic rainforests, the millennial yews to remnants of once vast hunting forests, discover over 300 places to visit, with spectacular photography, maps, coordinates and stories of ecology and folklore.

New from the award-winning Wild Guide, this explorer’s field guide allows you to find and experience the most magnificent living legends of the arboreal world.

- Millennial oaks surviving on rural estates

- Prehistoric yews finding sanctuary in our churchyards

- Rare fragments of once vast ancient forests

- Scattered open-grown trees in wood-pasture

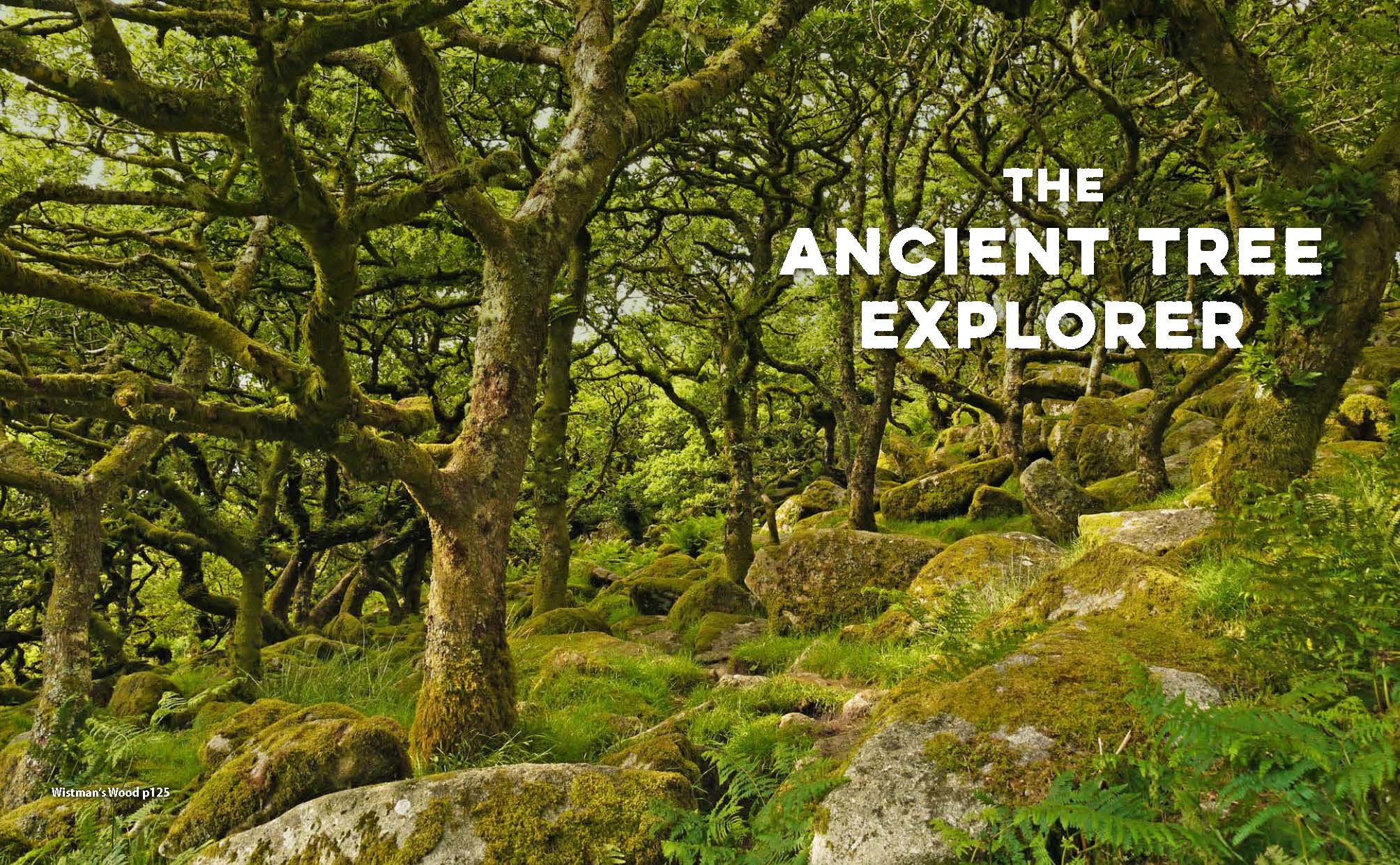

- Pockets of moss-rich Atlantic rainforest

- Granny pines from the once great woods of Caledonia

Britain is blessed with some of the most majestic and ancient trees in Europe. These trees and forests tell the story of our ancient landscapes; their legends and mythology reveal our past. Visit them and help preserve them for our future.

Julian Hight is an author, designer, photographer and musician. Julian has spent over 20 years documenting the ancient trees of Britain. He is author of four books and chairs Wessex Ancient Tree Forum.

Twenty years ago I embarked on a journey of discovery that would take me around the world in search of ancient, heritage trees. I visited over thirty countries across six of the seven continents (Antarctica’s fossilised trees having remained buried for the last 100,000 years, I decided to give them a miss.)

Even as a child, I had always held a fascination for old trees. Eight acres of woodland adjoined the housing estate where I grew up, so as well as playing on the street, my childhood friends and I played in the woods. It instilled in me a love of nature, trees and wildlife.

During my travels, I met some of the oldest, tallest and largest known trees in the world (all in the USA), legendary giant kauris in New Zealand, sacred camphors and cherry blossoms in Japan, worked groves of cork oaks and olive trees in the Mediterranean that have sustained people’s livelihoods for millennia, and many others in all their magnificent splendour. But it was the ancient trees of Britain, and their unique, open treescape – that captivated and enthralled me the most.

I lived not far from Windsor, and remember well the sense of awe and wonder I felt during my first encounter with the ancient oaks in the Great Park. It would be years before I learned of their international importance and great value to history, culture and biodiversity. On a school trip to Sherwood Forest, I met the mighty Major Oak – one of Britain’s oaken giants – and was totally absorbed by the stories and legends connected to it. ‘Robin Hood camped here with his merry men’, or so we were told.

Some thirty years later, I revisited after chancing upon a Victorian picture postcard of the tree. It was plain to see how the oak had retained its individual character, and was clearly recognisable over a century after the postcard was made. Little by little, my postcard collection grew. Visiting and photographing the subjects became a hobby. More than that – a (healthy) obsession. Being in the presence of these old sentinels made me feel good. A wholesome and natural experience, grounding me with a sense of place. Food for the soul.

As well as guiding me to the trees, the postcards provided records of visual dating. If the subjects had barely changed in over a century, then perhaps some of them may have lived for a millennium – just as so many poets and writers before me had proposed.

Ancient trees have long been celebrated through art and literature, in custom and religion. Their longevity has us holding them in high esteem. They offer a constant across time, are places where our forebears have met over generations, a link to our ancestry. They are living histories, having witnessed all manner of events through their long lives. I include some of their stories here.

Tales of Druids worshipping in sacred groves, stemming from Roman sources, loom large in the British psyche. In Japan, I witnessed firsthand Shinto worship of ancient trees – living shrines where spirits or kami are believed to dwell. Similar beliefs held by Māori, tribespeople of Africa and the Amazon, and many other ancient cultures leave little doubt in my mind that comparable faiths were once widely upheld around Britain’s ancient hollow trees.

Rarely found in dense woodlands, except where new woods and plantations have grown around them, Britain’s ancient trees are almost exclusively open-grown. They form part of an historic patchwork landscape, a long way from the dense closed-canopy woods of Britain’s collective consciousness, as depicted in Germanic ‘fairy tales’ that the nation was raised on.

Britain may have one of the lowest tree counts in Northern Europe, yet is thought to retain its highest number of ancient trees – especially oak and yew. The reasons for their survival are for the most part threefold: their economic value (where trees have earned their keep by providing fruit or sustainable timber through pollarding); as community assets (meeting places and boundary markers) and their religious value (such as yews in churchyards).

According to the Woodland Trust Ancient Tree Inventory, around 120 ancient oaks stand at over 9m in circumference. They are the elders and giants of the oak world, and survive in historic deer parks, remnants of ancient forests, wood pastures and commons, beside ancient roadways, on village greens and in hedgerows.

A similar number of yew trees – Britain’s longest-lived tree – are found mainly, although not exclusively, in Britain’s churchyards. Now rare in woodland groves, yew once featured more prominently outside the protection of the church wall.

It is these elder giants of the tree world that I have concentrated on in the listings of this book. When visiting the sites, I often call to mind the Japanese word: awaré. Used to describe an emotional response to transient beauty in nature, it has no direct English translation, although its meaning is surely universally understood. In sense and form it is similar to the English word aware. In the moment.

There are many fabulous books depicting ancient trees, but to my knowledge, no comprehensive guides are available. I hope this volume goes some way to resolve that issue. If I had owned a guide to ancient trees when I started, my journeys in search of them would have been made somewhat easier. I hope this guide helps you with your own journeys of discovery to some of Britain’s oldest and most majestic trees.