Publishes 1st April 2026 – order now for shipping in late March

By Margaret Dickinson and Philip Nice

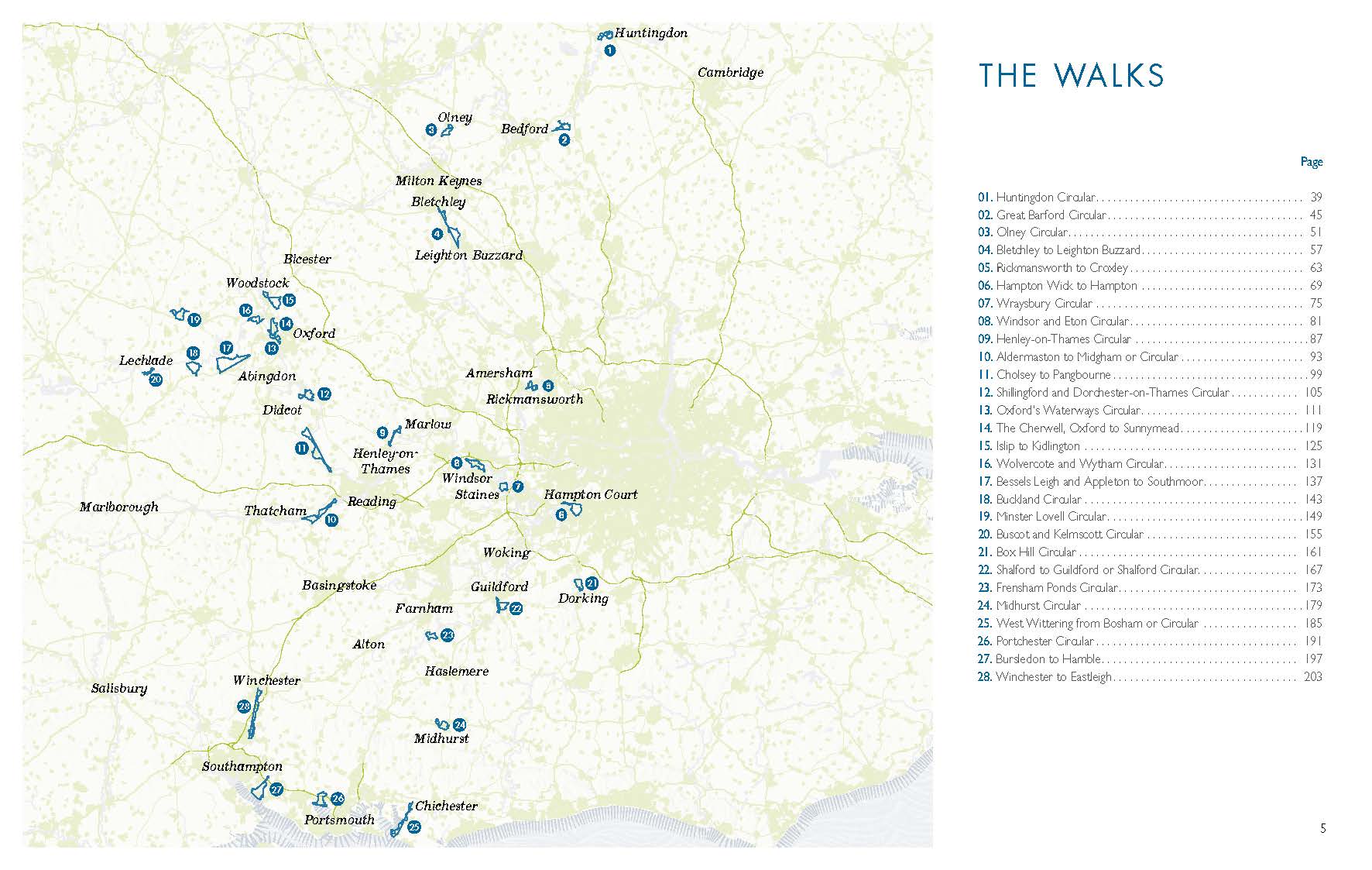

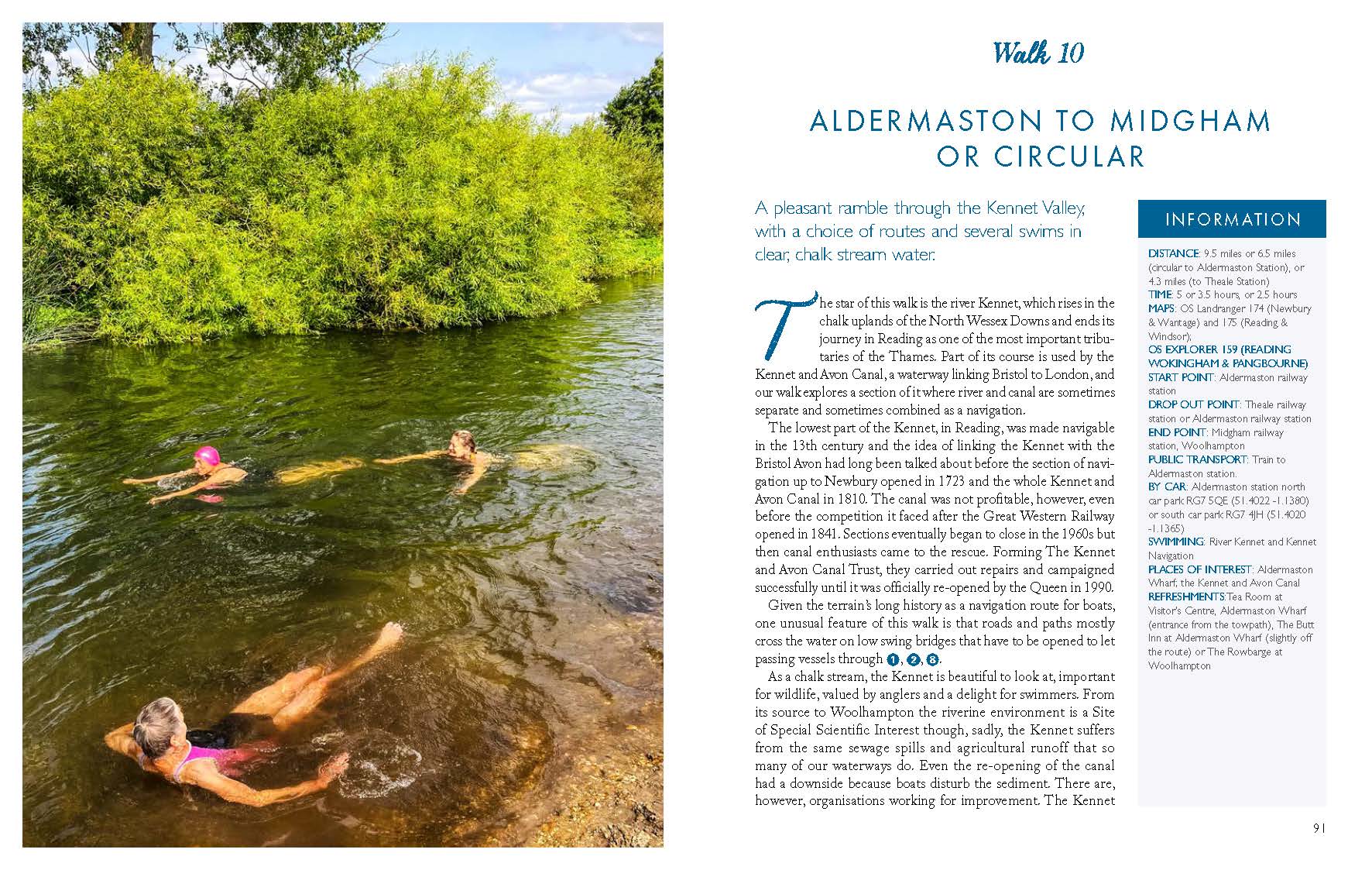

Wild Swimming Walks leads you on 28 adventures through the beautiful counties west of London. From the magnificent Thames to rare chalk streams, and from blue lagoons to sunny seaside resorts, you will swim and dip among medieval ruins, ancient trees and lush river pastures.

Complete with photos, maps and practical guidance, rich in local history and stories, this book will appeal to wild swimmers, family explorers, nature lovers and walkers alike.

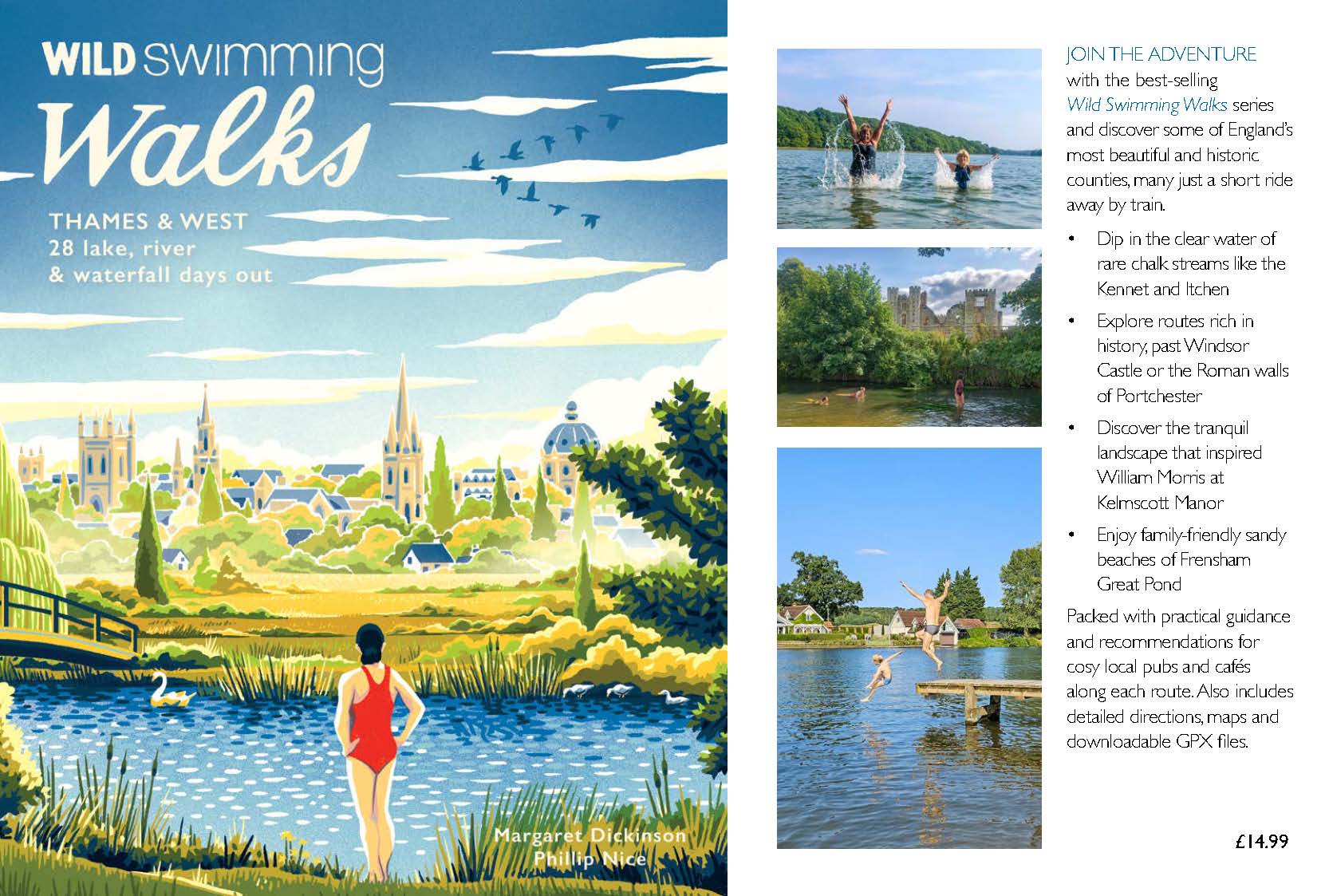

JOIN THE ADVENTURE with the best-selling Wild Swimming Walks series and discover some of England’s most beautiful and historic counties, many just a short ride away by train.

- Dip in the clear water of rare chalk streams like the Kennet and Itchen

- Explore routes rich in history, past Windsor Castle or the Roman walls of Portchester

- Discover the tranquil landscape that inspired William Morris at Kelmscott Manor

- Enjoy family-friendly sandy beaches of Frensham Great Pond

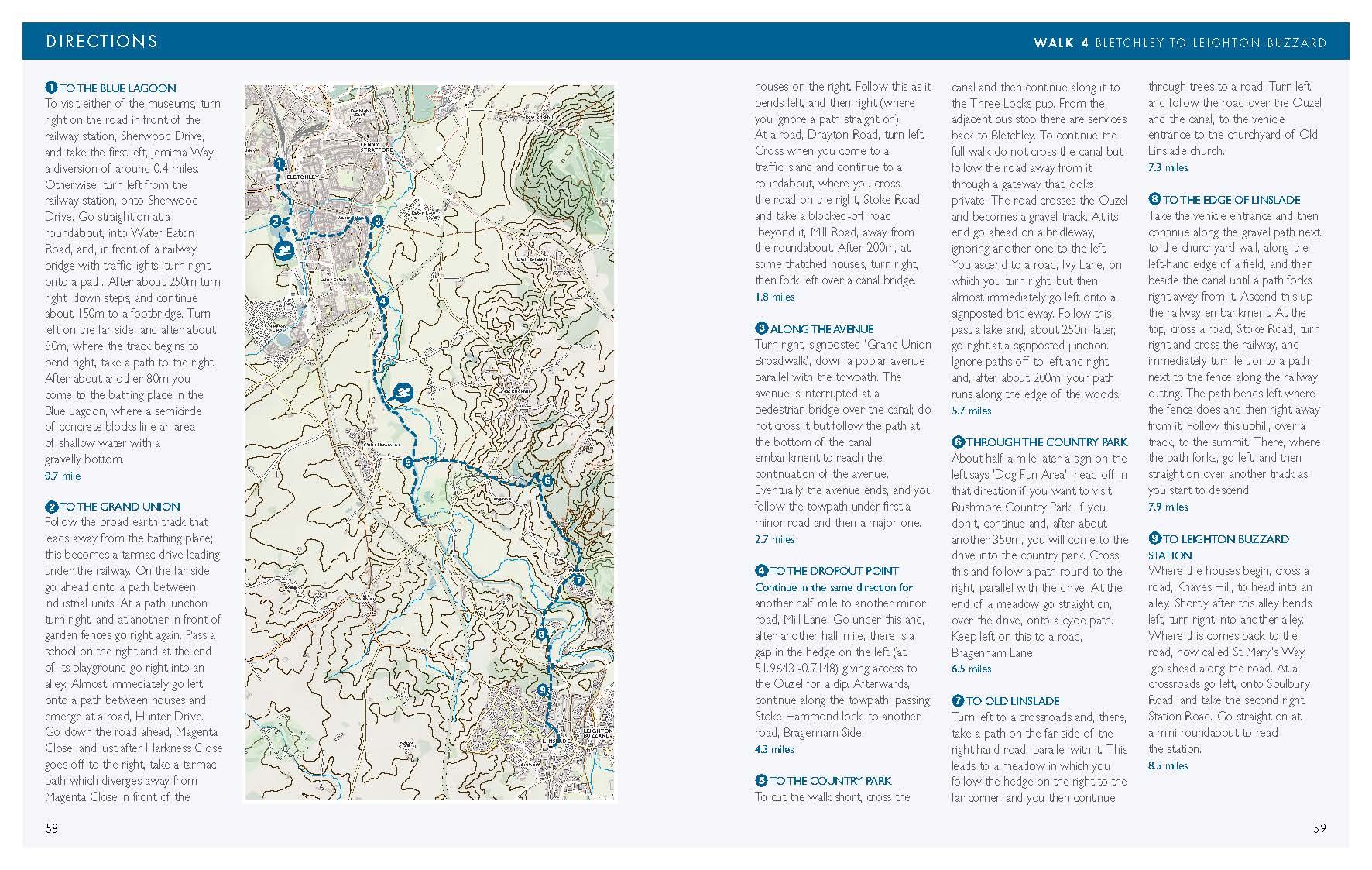

- Packed with practical guidance and recommendations for cosy local pubs and cafés along each route. Also includes detailed directions, maps and downloadable GPX files.

Margaret is a year-round wild swimmer, documentary filmmaker and writer who campaigned to save swimming at the Hampstead Heath ponds. Philip is a walk leader and guide, founder of the popular ‘Swim Walks’ Facebook community.

This book covers part of the heart of England, where the walks are embedded in classic English landscapes and pass some of the country’s most important cultural sites.

Geologically, this region consists of sedimentary rocks, generally chalk near London and to the southwest, and limestone to the northwest, with a band of sandstone in Surrey, overlain by river and marine deposits in the Thames Valley and along the coast. Limestone (of which chalk is a softer, finer-grained version) is formed chiefly from the skeletons of minute sea creatures, whereas sandstone, as the name implies, is formed from compacted sand. Depending on particle size, later deposits can consist of pebbles, mud, or clay. The chalk and sandstone layers were warped by the outer ripples of the movement that created the Alps and subsequently eroded to form long lines of fairly low hills, steep on one side – the scarp – and gentler on the other. This results in the Chilterns and the North and South Downs, impressive ridges of white chalk, the softer hills of golden limestone around Oxford at the edge of the Cotswolds, and the Greensand Ridge adjacent to the North Downs.

The rocks naturally influence the character of the rivers that carve their way through them. Those rivers that rise in the chalk hills not only look special, with their pale, pebbly beds, sparkling water, and trails of greenery that mimic bright green hair, but are also jealously guarded by anglers for their trout. Naturalists regard these rivers as particularly valuable because they and the ecosystems they create are unusual and globally very rare. In this book, these rivers include the Itchen, Colne, Chess, Gade, and Kennet, while the Thames, Cherwell, Mole, Ouzel, West Sussex Rother, and Wey flow over mud rather than being in direct contact with the underlying rocks and will never win prizes for limpidity. The Great Ouse and Windrush have intermediate clarity, greatly influenced by recent rainfall.

In this densely populated corner of England all rivers are subject to significant water extraction and, in return, receive large amounts of sewage (sometimes treated so well it is actually cleaner than water that never left the river, but as we all know, sometimes not treated at all).

The gentle scenery of green hills and wide valleys gives an impression of a stable, natural world – a somewhat deceptive impression given that almost everything you see has been shaped by human activity over a long period and only appears as it does because of ongoing human intervention. Almost all the rivers in which you swim have been deliberately altered – diverted, dammed, straightened, bridged – or unintentionally affected by livestock trampling the banks, by building works, or by developments elsewhere that draw off water in quantities that lower the whole water table. One kind of intervention often leads to another: when you build a bridge, you may have to deepen the river to ensure that floods do not carry the bridge away; if you straighten a section, you may need to build up the banks as well.

People in prehistory probably altered rivers, streams, and springs in small ways that left little or no trace, but in Britain, significant intervention dates back at least to the Roman period although little of the work done then has survived. Water mills began to be built again in the late Saxon period and by the time of the Norman conquest, they seem to have been quite common.

Rivers had long been important for navigation, and the first locks and weirs known in the UK were created in the 13th century. These were flashlocks which were much less navigation-friendly than the later pound locks we know today. A flashlock consisted of a kind of movable fence above a weir. It was made of boards called paddles, broad pieces of wood attached to long poles. These held the water when they were in place, making the river above them deeper, but they could be raised to allow a boat above the weir to shoot through on the rush of water released or to allow a boat below the weir to be laboriously winched up. They were not popular with millers because the water took a long time to rise again after the fence was put back and were often a source of tension between millers and bargemen. The pound locks in use today represent a significant advance because they have two gates, allowing a boat to enter through one gate, which is then closed, while water is gradually let in or out through the other gate, enabling the boat to be floated up or down with minimal effort, while leaving the depth of water above and below the lock unaffected. Interestingly, in terms of how a technology does or does not spread, pound locks had been used in China since the 10th century and were introduced in the Netherlands in the 11th but were not utilised in Britain until the 16th century. From around the 16th century also work was increasingly commissioned to straighten and deepen rivers to improve navigation. By the 18th century the network of canals began to take shape. Our walks visit some of the most important navigations – that is rivers that have been altered to make them navigable – and canals, which are completely artificial waterways. They include the Wey and Kennet Navigations, the Thames itself and the Grand Union Canal. Some proved uneconomical especially once they had to compete with railways, but at one time or another parts of all the rivers in the book were navigable except for the Chess, Gade, Ouzel and Windrush.

Although the waterways on these walks have been greatly interfered with, it is striking that they retain individual characters, so much so that it is difficult not to think of them as personalities. We may no longer believe they are gods or spirits but we continue to think and talk as if they are: they are ‘angry’ or ‘placid’, ‘welcoming,’ ‘reliable’ or ‘deceptive’ and as we get to know them we can come to love or fear them.

The land and waterways in our area have not only had a long relationship with humans but one that has been intensely studied for years. There were times during the research for these routes when the plethora of knowledge seemed daunting. Even tiny hamlets can have partially known histories dating back to the Bronze Age, and when it comes to major centres of culture like Oxford, Winchester, or Windsor the records are rich enough to inspire a steady stream of books. Though the area now seems the epitome of Home Counties placidity, not to say dullness, it was not always so. Whereas today local identities and loyalties have weakened and there is merely a gradual transition between the South-East and the Midlands or the West, there was a time when the Thames was a border between Saxon Wessex and Anglian Mercia. A little later, the Great Ouse was where Anglo-Saxons and Vikings met and fought. Once London had established firm control all the way to Wales, this strip of England with its fertile acres, gentle climate and proximity to the monarch at Windsor became home to many of the great families who controlled the kingdom and the merchants who prospered from its trade, together providing the funds to build many fine churches. However, when order broke down its location close to the capital inevitably placed it at the centre of conflict, including the war between Stephen and Matilda when the latter escaped dramatically from besieged Oxford, the Barons’ War when King John was forced to sign Magna Carta at Runnymede, the Wars of the Roses with the multiple battles of St Albans and Barnet, and the Civil War when London was staunchly parliamentarian while Oxford was the king’s headquarters. Later, the area sank into relative political obscurity but remained wealthy as a rich commuter belt for London. The information we have space for is a minuscule fraction of what is available and our selection is based on two simple principles: with a few exceptions, we only mention something if it can be seen from the walk; and we pick fragments of information that particularly appeal to us or that we think are of widespread general interest.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.